Lightning!

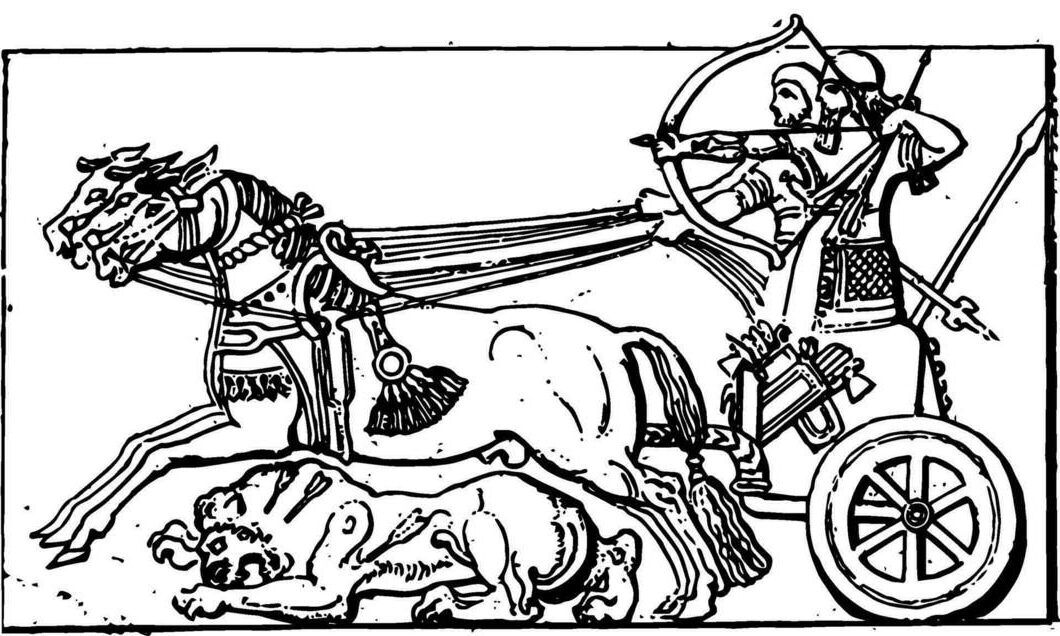

Assyrian Style

FAQ

You are looking at a assyrian inspired composite bow.

This bow combines a long draw, high performance, and high draw weights in a shorter design (55″-61″). It is long enough to comfortably accommodate the Mediterranean split-finger technique, making the horn bow accessible to the average archer who prefers not to use the traditional thumb draw.

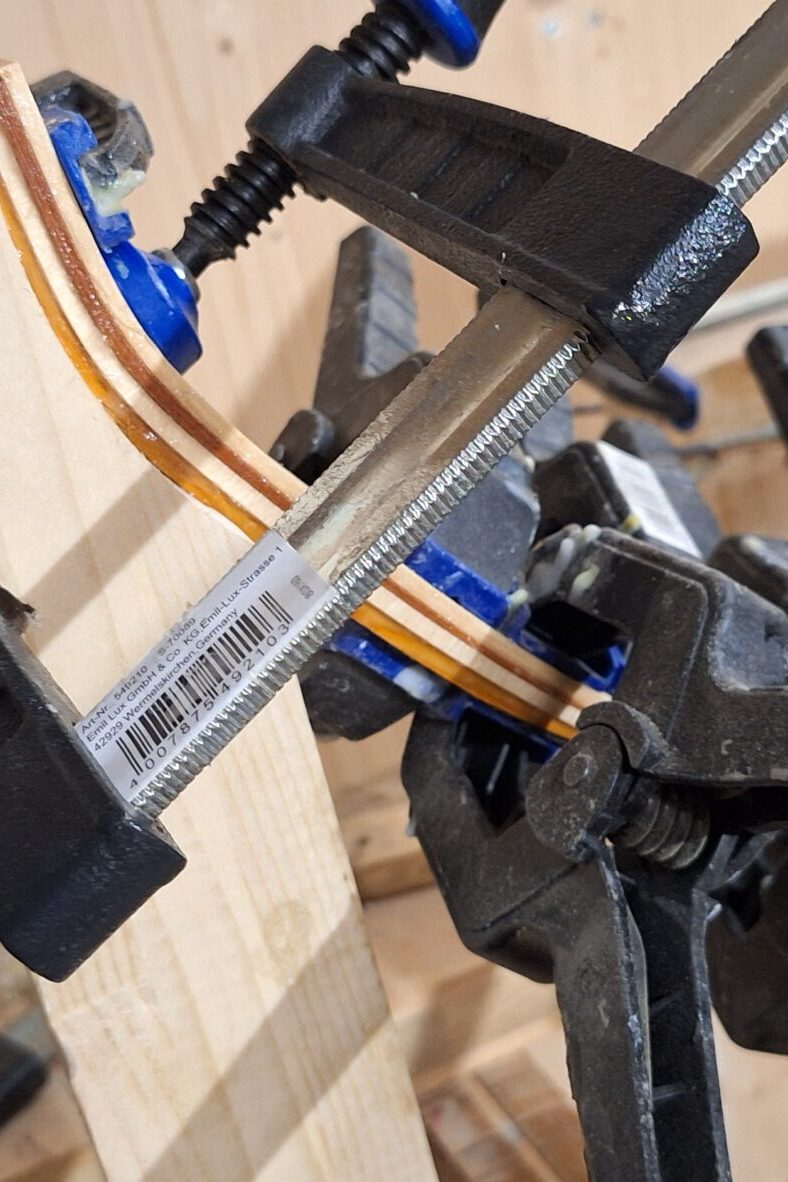

Made from: Wood – Buffalo Horn – Sinew & Hideglue

(wooden core is glued with modern glue)

Simple wooden bows have been around for at least 10,000 years – some even say for around 50,000 years. The composite bow as a more effective variant was probably first invented in the Neolithic period, possibly in the Bonze period.

Composite bows consist of a wooden core, which is reinforced on the belly with a strip of horn and on the back with a layer of sinew and glutinous glue. The horn on the belly is practically impervious to the compression forces that occur, while the sinew layer on the outside of the bow is extremely elastic and stretchable. This special construction allows the bow to be made shorter, stronger and faster, which proved to be very advantageous in hunting and warfare.

Most scientists see the origin of the horn bow in the Scythian nomadic peoples of the Eurasian steppe.This is supported by very old rock paintings,

which document the use of curved reflex bows from the Bronze Age at the latest. These Scythian bows were the measure of all things in the bow world for a long time and it was a very long time before other cultures were able to build bows of similar quality. The fact that the Scythian bow was not simply copied by other cultures is probably due to its extreme complexity and makes it a fascinating and unique piece of its time. Unfortunately, no Scythian bows have survived from the very early period. The oldest Scythian bow actually found dates back to the 4th century BC and was found in a grave in the Altai Mountains. The Scythian arch is also mentioned and described many times in ancient Greek mythology and is also depicted in pictures. Btw: The Scythian bow also is famous as the Cupid Bow!

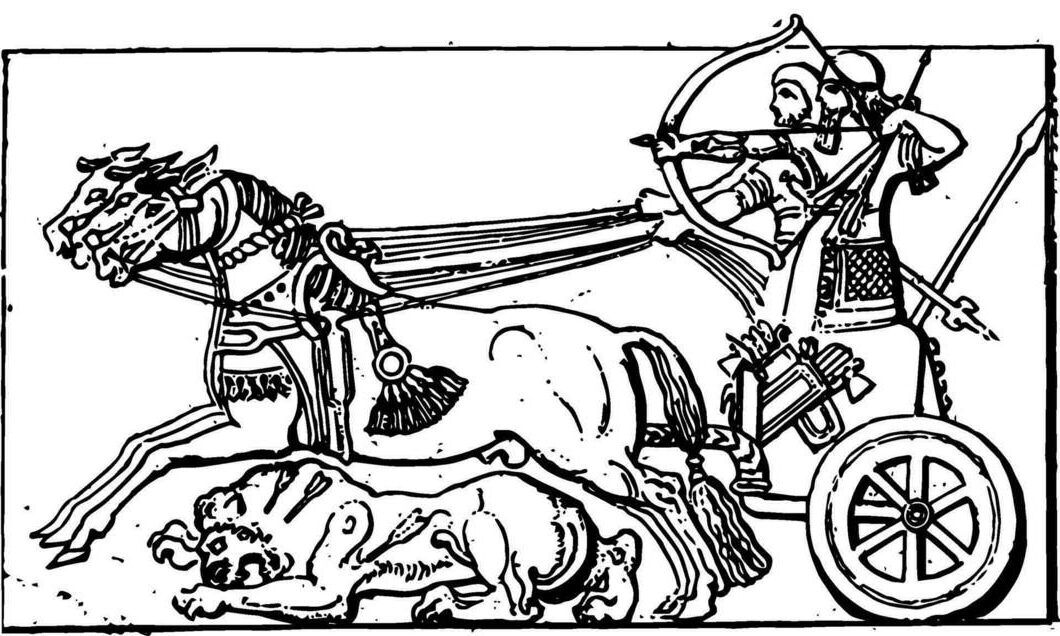

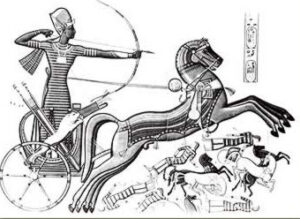

In the Fertile Crescent between the Euphrates and the Nile, particularly in ancient Egypt, horn-wood-sinew composite bows were being developed from a very early stage. These bows appear in large numbers and various forms in pictorial representations from this period, both in Egypt and among the Assyrians. However, such depictions are not always reliable in terms of scale and often incorporate artistic interpretation, meaning that conclusions about their exact appearance and specific construction methods are somewhat limited. In this context, the bows found in the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun are an extraordinary stroke of luck. Preserved in nearly working condition since around 1300 BC, they provide invaluable insights into their dimensions and construction. These findings also confirm that the Egyptian angular bow had little in common with the Scythian bow and must therefore be regarded as an independent development that established its own tradition.

A distinctive feature of the Egyptian angular bow is the pronounced deflex at the grip and in the middle third of the bow when unstrung, followed by a consistent reflex towards the ends—resembling the modern deflex-reflex longbow in shape. When strung, these bows form an almost equilateral triangle with their limbs fully extended, which is why they are referred to as “angular bows.” One of their key technical features was the deflex at the handle, which allowed for a very close bend and thus a longer draw length. Additionally, these bows had full bending limbs that bent into arc of circle at fulldraw. This design required particularly long pieces of horn from the Nubian oryx, which were likely difficult to obtain in large quantities. Furthermore, these bows had an extremely sophisticated internal structure, featuring a wooden core composed of multiple strips of wood, all meticulously aligned at right angles. Their construction was therefore significantly more complex and labor-intensive than that of later horn bows.

The Assyrian bow likely evolved gradually from the Egyptian angular bow. It is depicted in a very similar manner in contemporary artwork and may have looked almost identical to the Egyptian version when unstrung. However, a notable difference in some representations from this period is that, when strung, the Assyrian bow no longer forms a perfect triangle but retains a certain degree of reflex at the tips, preventing it from fully straightening even at full draw. If the limbs were not entirely bent at the ends, the bow’s performance improved, and it could also be made slightly shorter while maintaining the same draw length. A shorter bow with stiffer limb tips allowed for the use of shorter horn strips, making production easier and more cost-effective while also enhancing performance. Additionally, a more compact bow improved maneuverability, particularly when used from horseback or a chariot. Despite these refinements, the Assyrian bow was essentially an enhanced version of the Egyptian angular bow.

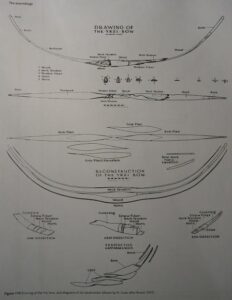

A truly fundamental innovation emerged with the discovery of the bow from Baghouz in modern-day Iraq. Known as the so-called Yrzi Bow, it has been attributed to Roman auxiliary troops from this region and introduced a groundbreaking feature: long, stiff limb tips. These limb tips, further reinforced with bone plates on the sides, appear to be early precursors of what later became known as siyahs or recurves.

Over time, word must have spread among bowyers in the region that such stiff tips, like those of the Yrzi Bow, offered a significant advantage. When combined with reflexed limbs, bows could suddenly be made shorter, making them even more powerful and easier to handle. This construction method, featuring separate siyahs, also reduced material constraints, as it required shorter pieces of horn and wood, thereby likely lowering production costs. Consequently, this type of horn bow soon appeared in various regional adaptations among the Mongols, Chinese, Indians, Tatars, Huns, Hungarians, Ottomans, and others. However, in Europe, traditional wooden self-bows remained the preferred choice. As these new bow designs spread, the Scythian bow eventually faded into obscurity. Its production may have ceased simply because it had become too complicated and expensive compared to its more efficient competitors—the technology of the Scythian bow was ultimately surpassed. Thus, a clear evolutionary progression can be observed, from the early Egyptian and Assyrian bows to the highly developed Ottoman and Korean bows, whereas the Scythian bow remains a historically unique outlier. The perfect replicas in the pic above made by Matthias Lehner wonderfully illustrates this early develpments between 300 AD 1200 AD.

This brief historical journey demonstrates that the Lightning! closely resembles early horn bow designs, particularly the Assyrian bow, both in appearance and construction. Like its historical counterpart, it is relatively long, features a deflex at the grip followed by an accentuated reflex towards the tips (though without actual siyahs), and possesses a complex wooden core structure.

disclaimer: this does not claim to be completely historically nor scientifically accurate and largely reflects the personal opinions and theories of a bowyer – not scientist.

I make these bows from 30 to 70 pounds of drawweight and up to 32″ of drawlength.

This bow is shorter than the Turbo!Longbow and has more reflex which of course makes it an even faster bow.

I haven’t done systematical speed testing yet with this bow; we once shot it through the chrono and got 200+fps with 8gpp.

In contrast to the Turbo! Longbow, this bow has a historical model and can therefore be shot in the Historical Class.

However, you can also get it with an arrow rest and shoot it with light carbon arrows in the TRB-class.

No. Compared to wooden bows this type is very forgiving. The Material has big reserves and does not fatigue. It does not care being strung over a longer time nor a higher brace.

However, the sinew layer on the back of the bow will make it a little lively sometimes. The reason is the sinew-layer that reacts to changments of the humidity in his surrounding. It will add some drawweight, reflex and efficiency in the dry winter-period and loose again with higher temps and humidity during the summer season. The owner will always have to keep a watchful eye on his bow and maybe sometimes the bowyer will have to do some small corrections.

Unlike classic hornbows there is no need to straighten or adjusting before shooting. Due to the high reflex I do however recommend stringing it with a stringer.

This bow is designed and built state of the art using the toughest and most exclusive natural materials available. Of course it’s coming with my standard 1 year warranty.

In Korea, where these hornbows have a long culture and are often family-owned, it is said that such a hornbow can be inherited once before a new one has to be purchased.

yes, its extremly pricey – but hey what doe’s it matter if you really want one – lol

Nobody.

I will sell those bows only to experienced archers and only sell with personal handover and instruction. If this is not possible, proof of suitability can also be provided by other means (sale sur dossier).